The content shared within this toolkit is a preliminary draft in preparation for release of a more comprehensive resource to be available to the university community in the coming months. For information on governance and oversight of microcredential initiatives at the University of Toronto please contact the Office of the Vice-Provost Academic Programs at vp.academicprograms@utoronto.ca.

Your feedback is welcome. Please share comments and suggestions on the content of the toolkit with Digital Learning Innovation at digital.learning@utoronto.ca.

WHAT ARE, AREN’T AND MIGHT BE MICROCREDENTIALS?

Frameworks created by eCampus Ontario, the Government of Ontario (2021) and UNESCO (2021), describe microcredentials as involving collaboration between an accredited educational institution and an employer/sector to identify, create and review workplace relevant training that is of value to the learner and the employer/industry sector.

employer/sector to identify, create and review workplace relevant training that is of value to the learner and the employer/industry sector.

The term ‘micro’ indicates shorter and possibly more specialized units of learning than what a learner will experience in something like a term-based credit course.

A ‘credential’ is that which is earned by a learner and serves as evidence of accomplished learning. This evidence may require some form of assessment.

In comparison to traditional courses and ways of learning that focus on structure and specific due dates for assessments, microcredentials value self-directed learning and anticipate that learners will complete smaller units of learning experiences at a pace that meets their learning needs and styles.

Microcredentials do not have to conform to usual University of Toronto term intakes and may be offered multiple times throughout the year, or in a self-paced format. In comparison to traditional courses, microcredentials can offer greater flexibility for learners.

Microcredentials have the potential to fill skills gaps in both the current and future labour markets and may give learners the opportunity to “specialize” in a particular area or topic. An hiring employer will know if a candidate has a specific skill set based on the microcredentials they completed.

Microcredentials are:

- Shorter learning experiences that relate to a specific topic or hone an identified skill gap in ways that are flexible and readily accessible for learners. This means there is variety of ways to offer and design microcredentials.

- Designed to focus on a specific skill, subject, or topic area; this focus differs based on the needs of the learners, employer, and industry partners.

- Credit-bearing or non-credit-bearing. The design of each micro-credential is contextual and should reflect the needs of specific learners, industries and professions, and University of Toronto programs.

- Skill-focused with applied assessments to support learners with training, upskilling, or pursuing a career or academic opportunity and verify achievement of competency.

- Developed and designed with partners or sector experts to ensure that training and upskilling accurately reflect workplace needs and are recognized with some form of certificate or digital badge verifying the learning outcomes or competencies that learners achieved.

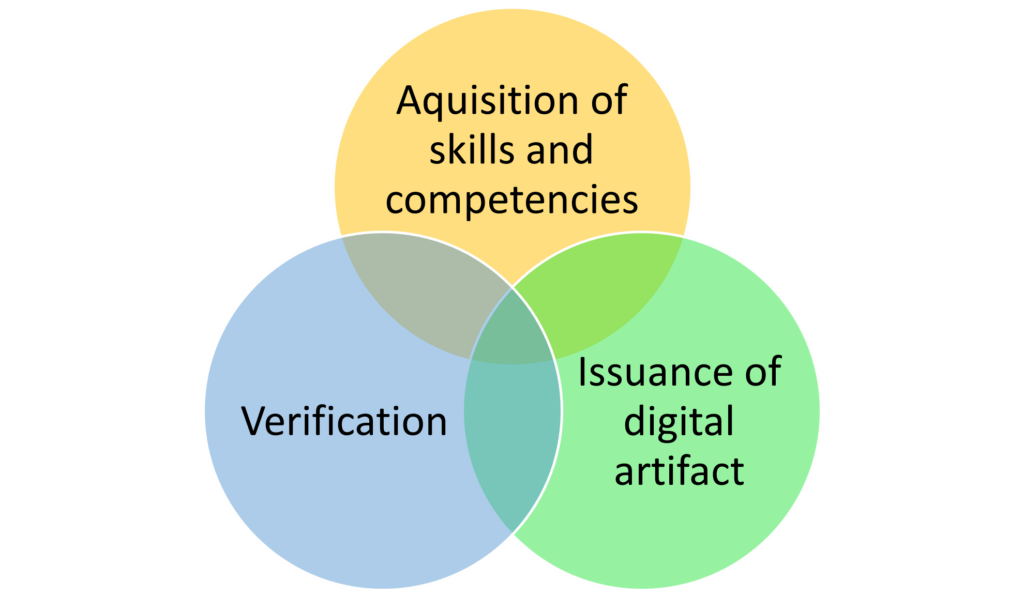

The following are common attributes shared by microcredentials:

At the University of Toronto, we anticipate that microcredentials should be designed as a high quality, interactive experience reflecting instructional design principles such as articulation of measurable competencies or learning outcomes. As well, the design should extend to instructional materials and resources, learning activities, and intentional assessments that support skill development. Design decisions will impact potential for inclusion in one or more learning pathways and potential for transferability—topics that should be discussed with and considered by program coordinators, sponsors and governance bodies. Similarly, clear expectations concerning grades or benchmarks (such as pass or fail) and methods of verification need to be developed.

Microcredentials should provide learners with opportunities to become proficient with a specific skill or competency. Opportunities to practice are valuable before the summative or final assessment, which determines if the learner has successfully mastered the particular skill or knowledge. Verification of the skill with an authentic assessment is a common characteristic of this type of learning program.

Microcredentials may be grouped, or “stacked” towards larger units of competence or capability, in a format that is verified, secure and shareable with peers, employers and educational providers. They normally certify achievement at a more granular, sub-course level and differ from traditional long-form credentials such as degrees and diplomas in that they are shorter, can be personalized and provide distinctive just-in-time value. They are also characterized by the issuance of a digital artefact, such as a digital badge, as an alternative to a traditional attestation of learning, such as a formal transcript.

Microcredentials offer the possibility of making higher education more convenient, flexible, and accessible and, in so doing, more inclusive and diverse.

References:

Selected content adapted from the following resources:

eCampusOntario’s Micro-credential Toolkit (2022) licensed by eCampusOntario under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Designing and Implementing Micro-Credentials: A Guide for Practitioners (2019) licensed by Commonwealth of Learning under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

MICRO-CREDENTIAL LIFECYCLE: FROM SUNRISE TO SUNSET

Outlined below are typical phases of the micro-credential lifecycle:![]()

- Ideation (sunrise)

- Feasibility review

- Design

- Approve

- Build

- Marketing and launch

- Deliver or pilot

- Evaluate and revise (sunset)

Each phase shares some key tasks and ideas that link to different parts of the microcredential ecosystem.

Ideas for new micro-credentials can arise from a variety of sources: a service-provider focused on a particular problem, an institutional, community, or learner need. Within the University of Toronto, all offerings that lead to a credential entail specific approval processes, which are outlined below in the “Approve” information.

Ideation

- Conduct gap analysis or market research to determine current training needs.

- Connect with local experts or partners within the profession or skill area to inquire if they are interested in participating in a working group or focus group.

- From these focus group sessions, determine what necessary skills, attributes, knowledge, or competencies are needed.

- Identify the purpose of a micro-credential, or what need the micro-credential will address.

Using a working group?

A working group can consist of smaller focus groups that can meet to draw out key information about the skill area or profession. Use focus group sessions to pose relevant questions to better understand the training needs, including upskilling or new skills that employees are lacking. Also, determine what the needs are for graduates from the University of Toronto and if they are entering into these work contexts with the correct skill set. If not, determine what exactly is missing and how a micro-credential could address this need.

You can gain this valuable information from your working group of professional experts; this group is critical to your ability to developing a micro-credential. Inclusion of subject experts and partners in the working group and participating in the focus group sessions, will provide valuable information for all stakeholders.

Feasibility review

- Consider how the micro-credential will align with institutional priorities (e.g., academic plan, strategic mandate agreements), institutional micro-credential policies, and unit plan resourcing prioritization. Build awareness, explore, and ideate possibilities for developing micro-credentials at your institution. Prepare a general project outline to share with key stakeholders.

- Identify a team of possible collaborators within your unit or within the university.

- Review necessary curricular and quality assurance processes, and indentify approval pathway for required approvals. Reach out early to the individual(s) responsible for approvals in your Faculty/Division, to ensure you have a full understanding of local requirements.

- Create an initial budget. Identify and apply for internal or external funding opportunities to support the design of the micro-credential. Consider learner and employer pricing sensitivity, and marketing plan and costs. Additional suggestions for costing are available in the Guidelines for Continuing, Professional and Executive Education.

Members of a micro-credential design team

Initiative lead: The lead is the lynchpin of the micro-credential development (is this you?). This person should be engaged about the initiative and be a good problem solver, able to navigate the internal processes.

Employer engagement lead: Getting employers on board early is critical. This person should have a track record of successful employer engagement and be able to talk their language and get calls returned.

Subject matter expert (SME): The SME co-creates content and advises on delivery in collaboration with industry or employer partners.

Pedagogical and edcuational technology support: This is an instructional designer or educational developer who can help shape the learning plan and content, possibly in partnership with your institution’s teaching and learning centre.

Visual design support: That first glance is crucial to respect and understanding. This person should be able to go beyond making the design attractive and correctly branded. The job is about how visual design can support the meaning of your micro-credentials.

Leadership champion: Sooner or later you’re going to need this person—someone at the director, dean, or vice-president level who believes in what you’re doing and can advocate at high levels.

Design

- Compile the list of competencies and skills and determine how a micro-credential can meet the requirements of the identified purpose it will address.

- With the focus group members, determine the number of instructional hours an employee or learner will need to master a specific skill or competency.

- Determine which learning goals or objectives need to be considered to ensure that learners can master a set skill or competency.

- As a group, determine what will be the best delivery method for this micro-credential: online, hybrid, or face-to-face.

- Build a learner profile to make informed decisions, including those of modality preference. Talk to prospective students about how to design a micro-credential to meet their needs.

Co-designing with industry

Having conversations with industry experts is essential and they must happen regularly. The more industry experts are involved, the more likely the content will be developed to meet their current needs.

Once this relationship has been established with industry experts, determine if any of them would be interested in writing the content for the micro- credential in collaboration with the faculty SME.

Approve

The University of Toronto has specific provisions for the approval of microcredentials. The pathway depends on whether the microcredential is intended to be offered “for-credit” or “not-for-credit” (i.e., not taken for credit towards a degree, diploma or for-credit certificate, and/or offerings that cannot be later applied towards a degree, diploma, for-credit certificate). In accordance with the Statement of Policy on Continuing Education, “the quality and level of the University’s continuing education courses and programs should be consistent with the University’s general objectives, and meet the same standards of excellence.” All continuing, professional and executive education activities offered in a division must be offered with the knowledge and approval of the Dean.

Not-for-credit microcredentials: See Guidelines for Continuing, Professional and Executive Education, especially section 4.1 Not-For-Credit Microcredentials.

For-credit microcredentials: See the University of Toronto Quality Assurance Process (UTQAP), especially section 4. Other Types of Academic Change.

Build

- If the micro-credential is competency-based, determine which learning objectives will help support the learner master the specific competency. If the credential is not competency-based, set learning outcomes and measurable learning objectives that will measure the micro-credential’s outcome.

- With the focus groups, identify how learners will be assessed and what evaluation method will be appropriate to determine whether a learner has successfully mastered a skill or competency. A mastery benchmark of passing must be determined by the working group; therefore, learners must pass the summative assessment with a specific percentage in order to be awarded the micro-credential.

Authentic Assessments and Micro-credentials

Focus group sessions should determine which authentic assessment will be suitable for a micro- credential. The goal is to ensure that the assessment accurately measures the stated competency for the micro-credential, and if there is no competency, then the stated learning outcomes and objectives. The goal of the assessment is to determine whether the learner can accurately fulfill the learning goals outlined in the micro-credential. Learners should be given clear instructions, criteria and a rubric on how to complete the required assessment.

Marketing and Launch

Once the micro-credential content has been developed and reviewed by the working group, and you know the assessment measures the stated learning goals, it is ready to be launched.

- Consider two key questions: What is the description of the micro-credential? Who is the audience?

- Complete audience research and analysis (e.g., use case personas).

- Conduct surveys with relevant audiences.

- Develop a website and marketing plan.

- Reach out to prospective students in person through class visits or events, website presence, and social media posts.

- Participate in sector-wide events for building bridges between sectors (e.g., eCampusOntario micro- credential forum), regional forums (e.g., City of Hamilton, Mohawk College, McMaster University Micro-credentials Community Forum).

- Collaboratively develop marketing materials such as one-pagers, video promos and tutorials, presentation templates, text copy for websites, surveys, website, brainstorming tools (e.g., badges in Canvas), etc.

Deliver or Pilot

The following are key concepts and best practices for piloting and delivering a micro-credential:

- Similar to other course development, an appropriate micro-credential outline and learning plan should be developed and readily available in the learning management system. The length of time a learner is given to complete a micro-credential must be stated in the outline.

- Micro-credentials that are stackable, recognized as transferrable, or create pathways to greater or larger credentials should be identified early on to the learners. For example, if three micro-credentials at 15 hours earns a learner three credits on their transcript, this should be identified and recognized as they consider pathways into other credential programs. Keep in mind that stackable microcredentials frequently entail changes to the greater or larger credentials with which they coordinate. These changes themselves require consultation and approval.

- If learners are successful, they are awarded the micro-credential, which can be showcased with an institution’s digital badge or certificate of completion or achievement. Learners should have some trackable record or transcript that outlines these micro-credentials, and if they are credit-bearing (not all are), including this information on a transcript would be appropriate.

- Learners may be given multiple attempts to complete their summative assessment. If they are unsuccessful on their first attempt, they consider providing constructive feedback from their facilitator, professor, or instructor on what they need to do on their second time to achieve a passing grade. Constructive, immediate feedback to learners is essential to help set them up for success.

- Explain to learners that, typically, after successfully completing an eligible course they will receive an electronic message with a link to their micro-credential.

- Encourage learners to share the micro-credential on your social media threads, such as LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, or to an e-portfolio or resume.

Prior learning and assessment recognition (PLAR)

Learners who believe they have already mastered the skill or competency that is being measured should be given an opportunity to measure their prior learning. The PLAR assessment should be the same summative assessment that is applied to learners taking the full micro-credential.

Flexibility for learners

Learners appreciate being able to work through micro-credentials at a pace that works best for them. Because micro-credentials are self-directed, a rigid learning plan outlining specific due dates should be avoided. in some cases, the only timeline for the end date of the micro-credential and when the summative assessment should be submitted. Therefore, once a learner has registered for a micro-credential, they should be informed right away of how long they have to complete the required learning activities and assessments. There should be time allowed for learners who require two attempts to complete an assessment: this includes time to provide them with appropriate and constructive feedback, and for the second attempt.

Evaluate and revise (sunset)

- Micro-credentials may encompass new skills that have not yet been integrated into degrees. As programs evolve to include these new skills, the sunset of a micro-credential may be triggered.

- Determine the life cycle of the micro-credential being offered. Depending on the purpose of a micro- credential, some may have hard expiry dates when the content is no longer up-to-date as determined by industry partners. Others may become out of date and require consistent content and curricular review to remain relevant.

- All University of Toronto microcredentials (for-credit and not-for-credit) are reviewed.

- For-credit microcredentials: the provisions for appropriate review are confirmed in the minor modification proposal as part of the approval process.

- Not-for-credit microcredentials: divisions determine the process by which offerings are reviewed periodically by the Dean.

Resources for Approval and Review

Guidelines for Continuing, Professional and Executive Education

Certificates (For Credit and Not-For-Credit), Policy on [February 25, 2016]

University of Toronto Quality Assurance Process (March 15, 2023)

Continuing Education, Statement of Policy on [November 15, 1988]

PLANNING THE PROGRAM

As with any new education initiative, the first step is to have a clear sense of what you are trying to achieve. Practitioners must be able to answer fundamental questions: “Why are we doing this?”; “What is our purpose or objective?”; “Who will be involved?”; “How will we go about it?”; and “How will we know whether we are successful?”

First, the Why

It is imperative to know why you want to develop microcredentials, which necessitates identifying the goals of your initiative. Are these, for example, to respond to student demand for more relevant future skills, to make learning personalized, to break it into smaller, bite-sized chunks, or perhaps to work more closely with industry to ensure graduates gain mastery of work-ready skills? The options are wide but not mutually exclusive. Understanding the strategic intent will help you describe the benefits to your stakeholders, particularly to key players such as the credential earners and the reviewers or consumers of the credentials (e.g., employers and other educational institutions).

Next, the Who

The golden rule applies when designing a new program — that is, know your audience or market. These are the learners and earners, whether they be school leavers, recent graduates, alumni, or mid-career employees looking to advance or pivot their career. They are not a homogenous group and will have some distinctive characteristics, but all share the common thread of being lifelong learners needing to fill skill gaps, upskill or reskill. Do your research and consider exploring market analysis to ensure the demand and audience is ready for your program.

Now, consider the How

After reaching a clear position on the first two questions, it is time to address the issue of how to build microcredentials and to cultivate the wider ecosystem. Consider what your preferred approach or methodology will be, to align with dviisional processes, culture and resources. Is it to be a small pilot, or will you collaborate with continuing education initiatives? Is there a sense of urgency to get going, or does a slower, more cautious approach fit better with the organizational culture? Will an agile approach, with rapid “test-and-learn” iterations, work well, or is longer term planning more appropriate? Is there an intention to work with external partners? The overall purpose and objective of the project will necessarily inform your preferred approach.

What does success look like?

The scope of your initiative will inform the success factors. What will success look like in the immediate, intermediate and long term? The success metrics should include impact, cost–benefit, strategic alignment and sustainability across the components of the ecosystem, measuring product quality and efficacy, learner and stakeholder experience, and industry and employer acceptance.

Designing micro-credentials: creating a scalable model

Micro-credential design warrants planning for the future as well as scoping out the immediate opportunity. It is important to consider more than the design for each stand-alone micro-credential Key factors are: determining the relationship between individual credentialed products and whether a hierarchy or other organising structure exists; assessing the size, duration or weight of each micro-credential; and mapping the micro-credentials against the relevant skills, competencies or capabilities.

Having an overarching schema adds rigour and value to the program by articulating a meaningful pathways for and minimizing the risk of inadvertently creating dead-end pathways or orphan courses.

Selected content adapted from the following resource:

Designing and Implementing Micro-Credentials: A Guide for Practitioners (2019) licensed by Commonwealth of Learning under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

SECTOR RELATIONS AND EMPLOYER-EDUCATOR PARTNERSHIPS

Many micro-credential initiatives are grounded in partnerships with a sector or with specific employers with whom the institution as an ongoing collaborative relationship. Engaging with external partners can support development of relevant learning pathways that include authentic practice activities and assessments that will be useful to learners in their future work.

Many micro-credential initiatives are grounded in partnerships with a sector or with specific employers with whom the institution as an ongoing collaborative relationship. Engaging with external partners can support development of relevant learning pathways that include authentic practice activities and assessments that will be useful to learners in their future work.

There are a few questions you should ask before you begin:

- What opportunities exist for more co-designed and cohesive partnerships?

- How can the employer organization or sector play an active role in co-designing and co-delivering micro-credentials to enable credible and relevant employee and employer forms of certification?

- What industry and professional forums can be used to help broker and facilitate meaningful co-design and co-delivery of micro-credentials (Mhichíl et al., 2021)?

These questions speak to the authenticity of micro-credentials.

Relationships between sector partners and educational institutions should be purposefully driven by two key elements: identifying in-demand skill or upskilling needs, and ensuring that any assessments are in line with job performance (eCampusOntario, 2020).

It is important to involve employers early on in the development. Contact North (2021) identified this as one of the 10 key actions needed to ensure micro-credentials meet the needs of learners and employers. Questions persist about whether students are being taught the skills they will need on the job market. There are varying levels of alignment, or misalignment, between employers’ desired topics and competency levels and what students are taught (Jones et al., 2019). While studies have found considerable overlap between the needs of employers and program focus, gaps have also been identified, especially in the area of self-management (Rhew et al., 2019).

Questions for employer partners

- Are we the right partner for this micro-credential? Can we actually do this?

- Is this going to help us? Does this align with our existing goals? Does it present us with a new goal that works for us?

- Do we currently have all the right skill sets to respond to this need? Are we willing to hire to get the required skill sets if we don’t have them now?

- Can we put our name behind the credential in a way that we are comfortable with?

There is great value in building employer-educator partnerships and collaborations. Educators can work with employers to undertake a needs analysis to identify a skill or competency with sufficient detail to develop a micro-credential. In turn, this can help employers identify discrete needs to support competency and skill-based micro-credentials (Franklin & Lytle, 2015). Tools are often needed to help support this work. For example, the ADDIE model can help design effective learning programs by moving five different phases: Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate (van Vulpen, 2020).

Tools to support employer-educator partnerships

Academy to Innovate HR (2020). Skills Gap Analysis: A how-to guide for Learning & Development. https://www.aihr.com/resources/AIHR_Skills_Gap_Analysis_L&D.pdf

Centre for Teaching Excellence. High Impact Practices (HIPs) or Engaged Learning Practices. University of Waterloo. https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/support/integrative- learning/high-impact-practices-hips-or-engaged-learning-practices

Kuh, G. D. (2008). Excerpt from High Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter. American Association of Colleges and Universities. https://secure.aacu.org/AACU/PubExcerpts/HIGHIMP.html

Niagara College Canada (2019). Finding and Cultivating EL Partners and Resources. Experiential Learning Toolkit. https://www.eltoolkit.ca/designing-experiential-learning-opportunities/ finding-and-cultivating-el-partners-and-resources/

van Vulpen, E. (2020, Oct.) How to Conduct a Training Needs Analysis: A Template and Example. Academy to Innovate HR. https://www.aihr.com/blog/training-needs-analysis/

Employer partners should understand how competencies are assessed so they are able to recognize the micro-credential as part of a validation of the skills of a potential employee. This can be done by engaging the employer in the process of determining which skills are most required as well as understanding the assessment process. The employer lens can highlight which skills are undeveloped in the available talent pool and where skills are migrating between two fields. In this way, academic rigour can work hand in hand with business needs in streamlining content development that makes learners more employable. It is particularly important to engage employer organizations or professional bodies in determining which skills and competencies will be assessed and how the assessment will be delivered

Industry input can influence content, delivery, and assessment of competencies that promote job-ready skills in a variety of ways. However, not all industry partners will want to be actively engaged at the same level. Different layers of engagement and collaboration with employers are possible; for example:

- Awareness

- Consultation (one-time, or pre- and post-micro-credential offering)

- Ongoing, intermittent advisory role (like a program advisory committee)

- Endorser

- Industry accreditor

- Supplier for industry-led micro-credentials

- Co-producer

- Industry-led quality assurance

Future directions to consider for educator-employer partnerships might include any of the following:

- Co-create protocols and rubrics for assessing work-integrated learning.

- Build ways to recognize non-formal credentials from employers (see the Credit Bank at Thompson Rivers University).

- Adapt and co-create competency frameworks with employers that can drive learning and recognition.

- Explore a contract training model, as practiced by Humber College in Canada, Otago Polytechnic in New Zealand, and VIA University College in Denmark: assess the workplace against a target framework, recognize current skills, identify gaps, and develop learning and recognition strategies for the workforce (Presant, 2020).

- Develop credentialed training for employers (managers) to be workplace assessors or advisors.

Instructional Design Modules

Visit our instructional design page for a series of interactive modules that guide and support the process for the design and development of microcredentials courses.

These modules include support for:

- Launching a Microcredential Design Process

- Identifying, Articulating, and Organizing Competencies for Microcredentials

- Demonstrating Competencies

- Engaging Students in Microcredential Experiences

Principles of instructional design consider how educational tools should be designed, created and delivered to any learning group. These modules will support the development high-quality microcredential courses that address the objectives of both student and educator. The content is primarily based on the backward design framework, which focuses on the process of learning, encouraging the instructor to think intentionally about how activities and assessment will ensure that the course goals and learning objectives are met.

Creating accessible and inclusive microcredential courses using universal design for learning principles

Introduction

An essential part of understanding your course context involves getting to know your learners, and this, in turn, involves being attuned to differences in their learning needs and expectations. A fundamental principle of effective instruction is to begin a course by meeting your learners where they are. One way to reach our audience where they are is to use the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) when developing microcredential courses.

UDL offers a set of principles for curriculum development that gives all individuals equal opportunities to learn. UDL provides a blueprint for creating instructional goals, methods, materials, and assessments that work for everyone. It is not a single, one-size-fits-all solution but rather flexible approaches that can be customized and adjusted for individual needs.

UDL principles can be applied to the overall design of a course and the specific instructional materials and strategies such as lectures, learning activities, learning resources, assignments, online instruction, and demonstrations. The goal is to provide learners with multiple or flexible ways of viewing or listening to information (representation), expression, and engagement, making a learning experience more inclusive and reducing the need for special accommodations for learners with disabilities.

In this document, we will provide checklists on three primary principles of UDL for microcredential design: 1) provide multiple means of engagement, 2) provide multiple means of representation, and 3) provide multiple means of expression and action. In each checklist, principles under each primary principle, checkpoints for each principle, examples of how the principles can be applied in the course, and resources to support readers in employing the principles for accessible and inclusive course design are provided.

Policy and the University of Toronto context

The University of Toronto (UofT) complies with the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) to make the university accessible and inclusive to all faculty members, staff, librarians, and learners. The university “strives to be an equitable and inclusive community and proactively seeks to increase diversity among its community members” (The Division of People Strategy, Equity & Culture, n.d.). In this context, all the training and materials should be produced and launched following the AODA legislation standard and consistent with the university’s commitment to embracing equity, diversity, and inclusion in pursuing academic excellence.

Please refer to the “Policy related resources” sub-section in the “Resources” section for more information concerning the AODA legislation standards and the UofT approaches and commitments.

UDL principles and checklists

This section provides a downloadable Word document with a brief description of each primary UDL principle. Each description is followed by a checklist containing all the principles and checkpoints, accompanied by examples of how the principles can be applied in microcredential design and course delivery.

It is important to note that an inclusive and accessible microcredential course in compliance with AODA legislation does not necessarily mean that the designer should put a checkmark on each checkpoint in the checklists. The listed checkpoints are merely items to consider in order to increase the inclusivity and accessibility of the course. Which checkpoints or principles are relevant is subject to the specific contexts in which the courses are embedded.

Multiple Means of Representation

Multiple Means of Action and Expression

Other resources

Policy related resources

Uoft AODA website (AODA legislation requirements, and the university initiatives and approaches, such as training and UDL learning to achieve accessibility)

Materials for accessible communication (As of January 1st, 2021, under the AODA, all public sector organizations must ensure their Internet websites and web content adhere to Level AA standards defined by the World Wide Web Consortium Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0. This website provides resources and further information for readers to ensure that their communication initiatives comply with the new requirements)

Other UDL resources

CAST online tools (CAST provided a wide range of online tools, many of which are free of charge, to educators who intend to apply UDL principles to increase accessibility and inclusivity of their courses)

Educator’s accessibility toolkit (This toolkit provides tips and best practices to make courses accessible and inclusive to all learners; the recommendations in the toolkit cover all UDL principles)

Examples in higher education (Examples of how the UDL principles can be applied to increase the inclusivity of teaching)

Introduction to accessible education (a general introduction to accessible education)

Mobile accessibility resources (This page displays a list of supportive software, applications, and tools for increasing the accessibility of the course content on mobile devices)

Real connections: making distance learning accessible to everyone (This article presents typical access barriers learners may face and recommendations for making the course more accessible)

SNOW Inclusive learning and education (This website provides a wide range of resources and tips on making classroom and course content accessible and inclusive to all learners)

Universal Design of Instruction (UDI): Definition, Principles, Guidelines, and Examples (Combined UDL and WCAG guidelines)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.